Venice Film Festival

Venice Film Festival

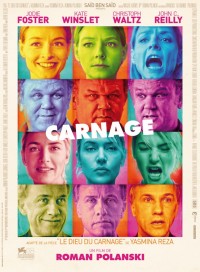

When the title of Yasmina Reza’s acclaimed 2006 play “God of Carnage” was given a haircut in its transition to the screen, it was hard to read what — if anything — the change implied about the film to come.

On the one hand, “Carnage” sounds pithier and more aggressive, removing the safety net of metaphor from a text already pretty unreserved in its examination of upper-class ugliness. On the other, shearing the title of any theological implications (though the play’s less-than-incendiary speech in which the titular phrase was coined survives intact) smacked of caution: would Polanski’s treatment blunt Reza’s scalpel, selecting some of the play’s less arguable social transgressions while leaving more troublesome ones on the stage? Or did Polanski simply like the one-word title better?

As it turns out, the mixed signals were a red herring either way: the newly godless “Carnage” stints neither on the bilious wit the play spewed on stage, nor the formality of its construction, which takes an hour to excavate raw animosity and dysfunction from yards of swaddled politesse. It is, in the final event, very much the play that critics and audiences swarmed around from its Paris debut in 2006, and such fans’ relative satisfaction or disappointment with it will hinge largely on their individual response to the wholly refreshed cast.

As with his well-acted but somewhat embalmed 1994 adaptation of Ariel Dorfman’s “Death and the Maiden,” the director hasn’t broken a sweat trying to Polanskify material that speaks very much to his sensibilities in the first place — it’s not hard to imagine the beleaguered auteur filtering his own exasperation at the hypocrisies of the bourgeois moral police, however obliquely, through that of Reza.

For those who aren’t approaching hat-in-hand, however, Polanski’s straight-ahead, self-effacingly stagy treatment has a tendency to magnify this grandly amusing play’s slight pettiness and narrowness of focus. Charting in real time (and efficiently-used real time at that, given the film’s tidy 79-minute length) the initially civil but gradually vindictive negotiations of four parents following a violent altercation between their pre-teen sons, “Carnage” is an unforgiving study of the faux-lefty principles and artfully masked materialism that prevail in privileged white society, but reveal themselves most crudely when misfortune strikes. (“My wife dressed me up as a liberal!” John C. Reilly’s overreaching store-owner yells at one point.)

For those who aren’t approaching hat-in-hand, however, Polanski’s straight-ahead, self-effacingly stagy treatment has a tendency to magnify this grandly amusing play’s slight pettiness and narrowness of focus. Charting in real time (and efficiently-used real time at that, given the film’s tidy 79-minute length) the initially civil but gradually vindictive negotiations of four parents following a violent altercation between their pre-teen sons, “Carnage” is an unforgiving study of the faux-lefty principles and artfully masked materialism that prevail in privileged white society, but reveal themselves most crudely when misfortune strikes. (“My wife dressed me up as a liberal!” John C. Reilly’s overreaching store-owner yells at one point.)

It’s thematic fodder that has inspired innumerable writers from F. Scott Fitzgerald to Edward Albee to Jonathan Franzen to Alan Ball, but Reza’s quartet of protagonists are all so irremediably unpleasant that her own tenets aren’t quite tested. This is occasionally fish-in-a-barrel stuff, however deliciously written, and the source’s lack of social or cultural particularity — the play was originally written and set in Paris, while the film takes the Broadway transfer’s lead of relocating it to the Upper East Side — doesn’t give it much resonance beyond the universal fun factor of milquetoasts behaving badly. In light of his tetchy (to put it diplomatically) relationship with the country, one might have expected Polanski’s first wholly American-set film since 1974’s “Chinatown” to take U.S. social politics a little more acidly to task, but the film’s verbal battle could still play out word-for-word in any plushly furnished living room in the world.

Deeper considerations aside, however, said battle is a gripping one — and if the characters themselves aren’t the largest of gifts to good actors, the dialogue they’re handed comes with a card and a bow. This is one-liner central, and a skilled match of actor to line can make certain words sing: “I don’t have a sense of humor and I don’t want one” isn’t even the sharpest of the film’s confessions, but when delivered by an actor as familiarly dour as Jodie Foster, it can’t fail to tickle.

As the prissiest and least self-aware of the four — “You get so absurdly attached to things,” she sheepishly self-scolds, all the while blow-drying a soiled coffee-table book — Foster is given the play’s most garlanded role, and enjoys herself most when the character at last self-immolates. If her rustiness is apparent in the subtler spots, she still fares better than Kate Winslet, here making a valiant stab at high-comedy nervous collapse, but too self-contained an actress (and arguably cast 10 years too early) to really make it fly.

The men, perhaps surprisingly, fare better. John C. Reilly is leaning a little on the mannerisms of his role’s Broadway occupant James Gandolfini, but plays delicately against the rhythms of onscreen spouse Foster. It’s Christoph Waltz, however, who most creatively interprets and restyles Reza’s brittle writing, and consequently walks off with the film: elegantly wielding a slippery Euro-Yank accent and maintaining a chilly calm when the remaining characters are pushed into hysteria, his indifferent, work-wed father is the most waspish of the four, yet somehow the closest the script comes to a sympathetic character — if only because he seems to be the only one aware how awful they all are.

The men, perhaps surprisingly, fare better. John C. Reilly is leaning a little on the mannerisms of his role’s Broadway occupant James Gandolfini, but plays delicately against the rhythms of onscreen spouse Foster. It’s Christoph Waltz, however, who most creatively interprets and restyles Reza’s brittle writing, and consequently walks off with the film: elegantly wielding a slippery Euro-Yank accent and maintaining a chilly calm when the remaining characters are pushed into hysteria, his indifferent, work-wed father is the most waspish of the four, yet somehow the closest the script comes to a sympathetic character — if only because he seems to be the only one aware how awful they all are.

Waltz’s surgically timed pauses and inadvertently louche appropriation of others’ space are responsible for the biggest laughs in “Carnage,” perhaps because they seem more explicitly scaled for the medium than anything else in the film. Polanski probably made the right choice in refusing to open the play out for the screen — save for a pedestrian pair of external bookend shots that needlessly contextualize the scrap between the otherwise invisible children — but Pawel Edelman’s lensing aims to outdo the intimacy of the theater experience by getting unflatteringly, claustrophobically close to the actors. It’s a tactic that seems a little over-compensatory when the single most striking shot in the film — a tableaux where all four are caught momentarily distracted from each other — could be contained within the proscenium arch. Swift and savage and so sparing in generosity that it risks selling its smart world-view a little short, the ample pleasures of “Carnage” (title notwithstanding) are those of its source, but it might have found more of its own.

[Image: Sony Pictures Classics]